Notes On Time and Visionary Experience in The Zone of Interest (Jonathan Glazer, 2023) and The Black Tower (John Smith, 1987)

“We can only solve the problem of time through sanctification of time.”

Abraham Joshua Heschel

“Where there is no vision, the people perish”

Proverbs 29:18

“The present is all lit up with eternal rays.”

CS Lewis

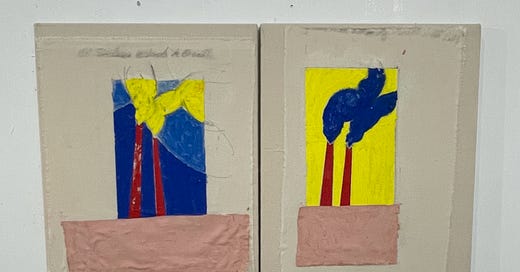

I made these two small paintings shortly after watching Jonathan Glazer’s new film, The Zone of Interest on New Year’s morning with a Hungarian art director who had an advance copy. She told me she'd been the first girl to become Bat Mitzvah at Budapest’s Dohány Street Synagogue since the Shoah. I haven’t heard any critics so far discuss what really drives the story in this film, which is the proposed transport of Hungary’s Jews to the gas chambers at Aushwitz in 1944 (a mission that the Nazi regime prioritised even to the detriment of its own war effort). This is after all the promised end that drives the story. While watching the film, I wondered if Jewish life could be an acceptable subject for an artwork, or whether there is only an audience for Jewish death. I thought about the peculiarities of antisemitism in the art world and, in this context, about what it might mean for a Jewish art to posit itself beyond the Shoah.

This whole question of what it means to be Jewish—and, more specifically, what it means to be a Jewish artist making work that wrestles with this question—is central to my own practice. That is, what it means to be a Jewish artist beyond the ‘everyone loves dead Jews’ paradigm. Maybe this is something more relevant to living as a British Jew where we are more closeted than in America. But I see my work in terms of a ‘coming out’ as Jewish. My work is trying to be like a beacon saying, ‘here I am, I’m a Jew, it’s cool, connect with me’. I’m coming out of the closet as a Jew.

What would it be like for an artist to find meaning in Jewish life rather than our death? (Or its footprints: neurosis, angst, paranoia, perversion, depression, gallows humour…)

Where is our Jewish life in The Zone of Interest? Pouring voicelessly out of tall and elegant chimneys that peer over an artificial wall into a clear cold German-Polish sky. Or in a flash of pale blue stripes moving through gaps in the undergrowth. The Jewish subject is permissible only as symbol.

But can we breathe life into a symbol, and thus render it a signal of transcendence?

Pouring voicelessly out of tall and elegant chimneys, a moment becomes an image which shatters time as mere duration and becomes our time. A tick is hanging in the air, waiting for a tock.

Two arms breathing over an artificial wall.

Who is breathing? Ruach. I wanted the painting to be so light—light enough to be a voice breathing. Light enough to carry me?

Can a symbol do that? Can an image of the horror that vacuum-packs our lives be made into a gesture of tenderness, hanging in the air, waiting for a tock?

The Hungarian poet Miklós Radnóti (1909-1944) was murdered in the Shoah. He wrote this poem in 1941:

In your two arms

I rock silently.

In my two arms

you rock in silence.

In your two arms

I am a child, sleeping.

In my two arms

you are a child, listening.

In your two arms

you enfold me

when I’m afraid.

In my two arms I enfold you

and I no longer fear.

In your two arms

even death’s silence

cannot frighten me.

In your two arms

I overcome death

as in a dream.

Can love overcome death? Can Jewish life overcome Jewish death as the proper subject for Art? As the chimneys appear in my painting, could I dare to ask such a question? I once dreamed two soldiers stood over me saying death had overcome me. When I awoke I was no longer alive, or at least not in any way I could recognise.

Can love overcome death, can the world be redeemed after the Shoah?

I remember Rabbi Lord Sacks zl speaking about the Rebbe:

“And how can you redeem a world that had witnessed Hitler? And the Rebbe did something absolutely extraordinary; he said to himself: if the Nazis searched out every Jew in hate, we will search out every Jew in love. This was the most radical response to the Holocaust ever conceived and I don't know if we still – if the Jewish world still – understands it.”

If I was searched out in love, would I be ready to say yes? Or would I feel harried by a question I hadn’t asked for?

Now I’m looking at John Smith’s film, The Black Tower. Jonathan Glazer’s towers reminded me.

Watching The Zone of Interest was the first thing I did this year (1/1/2024). The Black Tower was made the year I was born (1987). Miklós Radnóti was pretty much my age when they murdered him. Linear time, or-

I remember Glazer’s chimneys and become John Smith’s harried narrator. Like him, that first contact barely registers but it leaves a mark.

“It was from here that I first saw it. It’s crest protruding over the roofs on the other side of the road. Surprised that I hadn’t noticed it before, I wondered what it was, and then forgot about it for several weeks.”

But the tower keeps appearing—again and again—until it captures the whole of its narrator’s attention. He becomes rapt.

Eva Hoffman describes how “Dislocation exacerbates the consciousness of time.” Knowing time, we step out of its flow. But we look back through a veil of salt, longing to return. How can we learn to look forwards?

As the tower calls him to attention, he—its viewer—is torn from the usual flow of things and removed to the outside. Does repetition subjugate time, or sanctify it? If we are outside time’s flowing, are we outside of time per se? Or rather, are we washed into an eddy on linear time’s shore, more able to survey the fullness of the terrain?

John Smith’s narrator becomes agitated when the tower keeps appearing because such appearances can’t be verified for him. It follows that the repetition of encounters with the tower is powerfully dislocating. But why must its appearance be verified, why does the narrator so badly need someone else to have seen it? Why is it so necessary to keep a clean distinction between the empirical and the visionary, and thereby to sustain the idea that we are all in the same time experiencing the same reality? Is it to maintain faith in the idea that non-pathological experience (sanity) is unitary? And if I’m forced discover that reality isn’t unitary—when, for instance, a sinkhole appears in the sky—do I fall into a solipsism without end, and become unwell? Does the discovery that reality isn’t unitary necessitate a subjectivist descent into solipsism, or could we propose an alternative category? I would tentatively propose that we inhabit a context permeated by levels of revelation.

While non-viewers of the black tower flow freely in their linear experiences, John Smith’s narrator is caught in a loop in which recursiveness makes possible an experience of time concrete. Now I am outside normal life, outside of what reality can be expected to encompass. Where am I? With the unwell?

“I started walking home. One of my shoelaces had come undone and my shoe slipped uncomfortably against my heel as I walked. Outside St Mary’s Church I bent down to retie it and, looking up from the pavement again, I saw the tower behind the church roof. I panicked and started running, but when I got to the end of the street, the tower was there waiting for me. I turned the corner, saw it again. I kept running, taking different turnings, but whenever I looked up I saw the tower. Whichever way I ran it was always in front of me.”

The more the John Smith narrator’s attention is pulled into the tower’s gravitational field, the further he gets from our familiar world: that shared reality whose existence is both blessing and a consequence of tzimtzum.

Does the memory of the Shoah function this way, to the Jewish artist struggling to make a Jewish art? Everywhere I step, there it is, tearing a hole in our familiar world…

“Is this the promised end?/ Or image of that horror?”

A black hole or a celestial body?

I wonder: is our world familiar and our time free-flowing because the transcendent has withdrawn? What happens if it returns to puncture our day and our time? Perhaps such a puncture would transform the experience of time’s linear flow into a loop, as if the weight of the transcendent approaching here would bend our time into its field. I think it’s reasonable to propose that the transcendent has always been experienced (or intuited) through a loop. It’s not possible for the orbiting object to touch what is being orbited, but the quality (shape, speed, direction) of the orbit infers its presence. In Chassidut perhaps we could understand yearning and longing as a kind of orbital action.

“…the heart can never approach the spring, but ever stands opposite it and looks at in longing.” (Rabbi Nachman)

In the same way that the particularities of an organism can be seen to infer the environment in which it has evolved, can we intuit a celestial object by studying an object in its orbit? Does a year sound out our sun?

The Jewish year revolves around the loop of Torah. On Simchat Torah we read the closing verses of Deuteronomy and then immediately start again at the beginning with the opening lines of Genesis. The annual cycle concludes with Moses looking out at the promised land across the desert in the distance. He knows he’s about to die and that he’ll never get there. And he’s just standing up looking out at it. And then he passes away.

Never again has there arisen in Israel a prophet like Moses who knew YHWH face to face (לכל), in regard to all the signs and portents that YHWH sent to him to display in Egypt against Pharaoh and all his servants, and his whole country, (ולכל), and for all of his strength of hand, and for all of his great wonder that which Moses did before the eyes of all of Israel. (Deuteronomy 34).

The Torah ends there. Even in the moment of death, Moses’ eyes remain open—the light never deserts him, “when he died; his eye was not dim, nor his natural force abated”. And then we start from the beginning, at the first creative act in Genesis: let there be light. It comes full circle—the journey begins again. The light persists and insists.

But last Simchat Torah, on October 7th 2023-

Is The Zone of Interest the first film to sound out its subject by focusing on the negative space around it? Watching the film is then like an orbital journey around an absence whose presence can only be intuited - to push the analogy further - by experiencing its strong gravitational field ‘warping the fabric of space-time’. Is this how Glazer is able to make the void speak, make darkness visible?

Who could sit and watch this film and declare that what we see in the frame is more real than what we are called to imagine, but remains elsewhere outside the frame. His film exists to give that absence weight; all its power and pathos depends on this. Without experiencing this ‘weight of absence’ the film would cease to function. So we might say that The Zone of Interest offers a truly metaphysical cinematic experience. It teaches us that some subjects exceed our grasp: that words fail, pictures too. When such a subject exceeds our frames we can only gesture towards it by focusing on its weight of absence. Glazer shows how what we envision can be more true than what we see with our own eyes.

What we see in his film is artificial—the art director I watched it with couldn’t accept the obvious artifice of the camp wall. But I would insist this artifice is an essential part of Glazer’s vision—what we imagine (or intuit) is true. What we see and sense in the film is illusion, what we circle around is the real.

“I stared at the space where the black tower had been, trying to collect my thoughts. Two boys came by eating chips. I tried to ask them about the tower but they ran away before I could finish my sentence. I stopped a woman pushing a pram full of groceries, but she ignored me completely. I started walking home.”

As the viewer of the black tower, John Smith’s narrator is tainted and becomes a pariah, shunned by the public. Two boys run away from him. A woman ignores him completely. The taint persists in the form of a question no-one can answer. He asks, ‘Have you seen the tower?’

“I tried to ask them about the tower but they ran away before I could finish my sentence.”

What is the answer John Smith needs to hear? Is it: “Yes, I know exactly the tower you mean, it’s the water tower at Langthorne Hospital”? Or is it simply, “Yes”?

Martin Buber writes:

“Man wishes to be confirmed in his being by man, and wishes to have a presence in the being of the other… Secretly and bashfully he watches for a YES which allows him to be and which can come to him only from one human person to another.”

“He watches for a yes”. There are different ways of seeing. Can we see a “Yes” in Glazer’s chimneys? Can I, following the Rebbe, attend to such horror with love? Confronted with mystery we plunge towards crisis as a black square appears puncturing normal life, demanding answers.

Is that black square a solid wall to bang our heads against, or a door to step through?

Does repetition subjugate our time, or sanctify it?

Not, ‘what is it?’, for which there can be no answer and only an endless loop of questions (a wall).

But, ‘will I step through it?’, for which an answer can be: ‘Yes’ (a door).

In interviews John Smith describes how he decided to make the film after noticing the tower whilst on a walk near his home. It was the unreflective black paint used on the wooden structure at the top that caught his attention. It looked like a void on a plinth, a hole in creation. Did John become unwell? Is it a vision only in so far as you attend to that possibility? Does the vision necessarily crush our attention into itself, or can we remain steadfast with eyes open and alert? A black hole or a celestial body?

Halfway through the film John Smith’s narrator becomes fully trapped:

“It seemed as though I would have to stay at home from now on, as there was little doubt that I would encounter the tower again if I went out. I resigned myself to my fate.”

On the soundtrack we hear a clock ticking. Meanwhile the narration confirms its suffocating turn inwards, resorting to the formal strategy of meta-narrative:

“The days passed quickly at first, as I was spending most of my time working on this script. Writing had never come easily to me and I found the pacing of dramatic fiction extremely challenging. In some ways I appreciated my incarceration because it forced me to keep working.”

“I started to lose track of time and spent months sitting at my desk staring out of the window. Always downwards, in case the familiar shape appeared over the rooftops. I took to wearing a cap with a large peak, so that there was no danger of the tower appearing at the periphery of my vision.”

Unwilling to look outwards at an encounter that challenges his assumptions about the world by dissolving the hard boundary between subject and object— and that therefore cannot be integrated within his existing meaning-universe—Smith decides instead to turn inwards and withdraw into his own navel (a black hole?). The film-logic follows, moving its focus of attention from ‘out at the world’ to ‘in on itself’, with a banal reiteration of its own mechanics.

Smith attempts to disguise this dead-end with a kind of wryly humorous intellectualism. But another way of seeing this is a man—and an art object—retreating from a reality that refuses to be reduced within the acceptable limits of Smith’s secular materialism. Formal inventiveness now becomes a kind of angsty petulance in the face of an encounter that arrives to challenge those limits. As the transcendent intrudes into Smith’s day, it must be straight-jacketed by the formalist creed of the London Filmmaker’s Co-operative.

Two minutes of cutting and splicing follow as John Smith idly plays with the view from his window, through the bars of his cage. Is it end of cinema, or an image of that horror?

Or is it more fair to see this as an attempt to image time itself? A bare winter trunk spliced into a tree in full leaf. A car rushing behind and disappearing into the hole the trunk leaves in the frame. A different car appearing out if it. After his encounters with the black tower we are presented with a complete breakdown in linear time. But for John Smith, this is also a complete breakdown. The clock resumes ticking as the screen goes black and the narrator continues:

“I don’t know who called the ambulance but I was glad when it arrived. At first I thought it was the ice cream van, and wondered why it was playing a different tune. When we arrived at the hospital, I was not surprised by the architecture.”

“My recovery took several months but the doctors were sympathetic, and for the first time I was able to talk about the tower in detail, without feeling that my audience would like to change the subject. As the weeks went by my obsession diminished, and by the time I was discharged it had become clear to me that the tower had only existed in my mind.”

Leaving hospital, Smith’s narrator is relieved to return into the linear flow of normal life, the unitarity of non-pathological experience (lol). The readmission fee is submission to the hard boundary between subject and object: “the tower had only existed in my mind” [my italics].

But what does it mean for something to “only exist in my mind”? Is this the ultimate trick of secular materialism: a superstitious belief in an objectively material universe that is the only really real, inside of which the subjective imagination functions like a projectionist of convincing fictions?

Upon leaving hospital Smith’s narrator goes up country to recuperate:

“It was suggested that I should convalesce in the country, so I arranged to visit some friends in Shropshire.”

“The weather was fine so I spent most of my time exploring the countryside.”

As the tower recurs, might we venture to say that the mind and the world out there exist within a continuum, across which we can chart levels of revelation?

Could we say that the visionary moment is that critical point at which the subjective pitches up and coalesces with the objective? We call the moment subjective experience coalesces with the objective: prophetic. It is precisely this: a moment, ie. a particular kind of experience of time.

“Everyone will admit that the Grand Canyon is more awe-inspiring than a trench. Everyone knows the difference between a worm and an eagle. But how many of us have a similar discretion for the diversity of time? The historian Ranke claimed that every age is equally near to God. Yet Jewish tradition claims that there is a hierarchy of moments within time, that all ages are not alike. Man may pray to God equally at all places, but God does not speak to man equally at all times. At a certain moment, for example, the spirit of prophecy departed from Israel.” (Abraham Joshua Heschel, The Sabbath)

For secular materialism to maintain its superstitions, it’s necessary to wave this away with ‘it’s all in the mind’. But the truth insists.

“I didn’t feel afraid when I saw the tower again. Instead, I could only laugh because it looked so absurd peering at me through the trees. I felt my old curiosity returning. I wondered how it had found me. I made my way through the woods and came upon the tower standing alone in a clearing.”

“It was even bigger than I’d imagined, and then close up it showed signs of age and decay, which had been indistinguishable at a distance.”

Rather than turning away in panic, Smith’s narrator this time is steadfast and, with eyes open and alert, he approaches the tower and becomes intimate with its particularities. The camera’s gaze softens, slows down and exhales. We no longer have the erratic jump cuts, but a gentle pawing at the tower’s surface. ‘Knowing’ as ‘objective knowledge’ is sidestepped and becomes an ‘intimate knowledge’:

In Yada ידע

An epistemology is thrust aside by an erotics.

הוֹצִיאֵ֣ם אֵלֵ֔ינוּ וְנֵדְעָ֖ה אֹתָֽם

Bring them out to us, that we may know them" [my italics]

Genesis 19:5